This week, Cemex announced what it called a 'groundbreaking' technology to fully decarbonise the cement production process by working with Synhelion on a solar-heated kiln. The process aims not only to reduce the use of fossil fuels but to turn CO2 into synthetic drop in-fuels such as kerosene, diesel and gasoline.

Such a technology leap would seem revolutionary for the cement sector with high energy costs and a pressing need to lower its CO2 emissions and to become a carbon neural industry. Cemex is targeting a pilot installation to begin operation with the Synhelion technology at an existing Cemex plant by the end of 2022.

Synhelion technology

Synhelion is a clean energy company evolved from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) in 2016. The solutions of Synhelion leverage high-temperature solar heat to radically decarbonise industrial processes and turn CO2 into fuel.

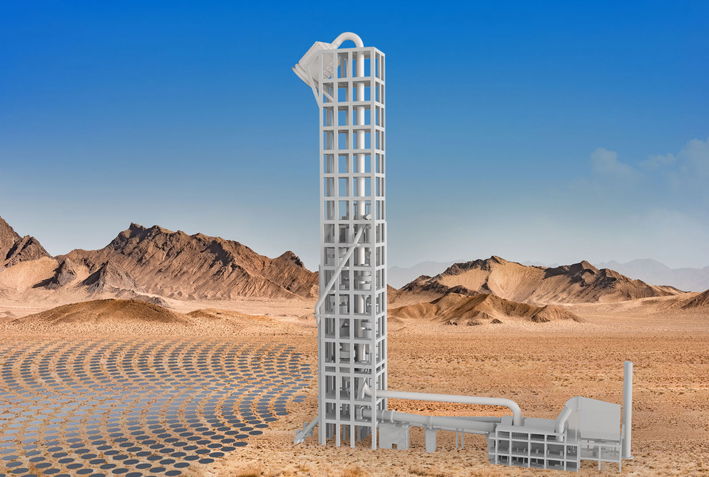

For the Cemex project, Synhelion will heat a gaseous heat transfer fluid (HTF) composed of CO2 and H2O in its receiver located on a solar tower on top of a traditional preheater tower. The HTF will drive the pyroprocessing of the kiln for calcination and emissions will be collected as the gases mix with the HTF. Thermal energy storage will enable 24/7 operation of the cement plant.

Solar research

Research into solar power in the cement industry is not new. To date, it hasn't led to commercial solutions that can be widely accepted by the industry. In 2007, for example, Holcim initiated a research project with the Solar technology Laboratory of the Paul Scherrer Institute and the Professorship of Renewable Energy Carriers at ETH Zurich, Switzerland. The project investigated high-temperature solar heat upgrading low-grade carbonaceous feedstock to produce high-quality synthetic gas to be used to substitute fossil fuels in the kiln.

Solpart H2020

More recently, in 2018-19, Solpart technology was employed at the Promes testing lab in Odeillo in the French Pyrenees which was capable of producing temperatures of up to 3000˚C. The project finally completed a 50kW solar reactor at Promes. The big challenge was in developing a reactor system that could feed through not just lime and cement particles but also non-metallic minerals like gypsum and meta-kaolinite and phosphate.

The Solpart H2020 project was also tested at a lab-scale at the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) of Solar Research in Cologne, Germany. Here the programme looked at demonstrating the reliable, multi-hour operation of the reactor, spread over several days. The programme trialled both a rotary kiln and a bubbling fluidised bed reactor for calcination.

Scaling up from a few dozen kilograms of rock to calcining several thousand tonnes of clinker per day is an ongoing challenge. The positive outcome of the Solpart trials was that it demonstrated that the solar rotary kiln was highly robust and capable of reliably heating particles to temperatures up to 1100˚C and achieve calcination. The Solpart project aims to create a partially solar-powered cement plant in Spain by 2025.

Heliogen project

A current project in the United States, funded in part by Bill Gates, is also looking at developing solar technology to power a cement kiln. Heliogen's Heliomax™ technology is being trialled in the Mojave Desert and uses 400 giant mirrors (multi-acre magnifying glass) to produce temperatures of 1800˚C. Heliomax™ technology points the mirrors to ultimately focus 300kW onto a small black, silicon carbide plate that is no bigger than a basketball hoop.

Bill Gross, Heliogen's CEO, admits that a limitation with the Heliogen project is that the world's cement plants don’t have enough land to erect Heliomax™ systems with hundreds of mirrors. However, there are opportunities for carbon capture with Helioheat™ as its system produces pure CO2 which is easier to capture than the dirtier emissions from fossil-fuel-powered kilns. Helioheat™ replaces fossil fuels by using the energy stored from the Heliomax™ capture of the sun’s energy rays.

Summary

The concept of solar powered kilns has proved difficult to scale up and Jan Baeyens, Solpart's Managing Director, believes a fully solar-powered cement plant is doubtful, but it is tangible that merging solar energy with alternative fuels such as biomass will be possible. The potential of solar energised cement kilns remains the topic of research and trials, but with Cemex and other private research bodies trying to solve the limitations of these systems the cement industry may well see further progress in this area. More tie-ups with leading technology companies and the cement sector will become more common. If the cement sector is to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 it has to accelerate its investigation into the best possibilities for reducing its CO2 footprint and the solar kiln may yet have a significant contribution to make in some parts of the world.

Synhelion and Cemex's model of a solar cement plant